TWE #28: How to reclaim our most important physical capacity

Read time: 5 minutes

As we age, our ability to move and stay independent declines.

Most of us probably associate this with losses of both muscle mass and strength.

But there's another lesser-known physical capacity that succumbs to ageing.

And this more profoundly affects not only our ability to carry out daily tasks, but our risk of negative health outcomes (like falls).

It’s muscle power.

So what exactly is muscle power, why is important, and what can we do about it?

To understand muscle power, it helps to contrast it with strength.

Strength is simply our ability to produce force.

By constrast, power is how quickly force can be produced.

In other words, power is the combination of force and velocity (or strength and speed).

This distinction is important, because we don't often need to produce a maximum amount of force (akin to our peak strength) in daily life.

Instead, everyday tasks like rising from a chair or climbing stairs require us to produce smaller amounts of force very quickly.

That’s why a number have studies have shown muscle power explains an older persons’ ability to walk, maintain balance, or rise from a chair.

And even more so than levels of strength or muscle mass.

Declines in muscle power with ageing outpace that of strength

The importance of muscle power becomes more apparent when we consider we lose this capacity much earlier - and faster - than strength or muscle mass.

Some estimates suggest muscle power is lost up to eight times faster than muscle mass.

Take this study comparing losses of muscle mass, strength, and power over 3 years in mobility-limited older adults (aged about 77):

And these declines say a lot about our risk of adverse health outcomes.

A recent study found older adults with low muscle power were almost 2.5 times more likely to experience falls and fractures compared to those wither higher muscle power.

The study also found muscle power better predicted those who would go on to fall or fracture than either strength or walking speed.

Together this showcases muscle power as a “vital sign” of our ability to stay independent and avoid negative outcomes across the lifespan.

Why does power decrease so much with ageing?

Changes in our physiology as we age reduce our ability to produce force quickly.

These changes include:

- A selective loss of the “faster” muscle fibres (known as type II fibres)

- Reduced speed of key enzymes involved in muscle contraction

- Compromised "drive" from the nervous system to muscles

- Greater activity of opposing (antagonist) muscles during movement

Ultimately this makes it harder for muscles to contract and produce force quickly.

The good news?

It’s possible to at least partially reverse these deficits, and in turn, restore physical function.

No matter how old we are.

So how do we improve muscle power?

Because power is the product of force and velocity, declines in either of these capacities may reduce power.

The flipside is that improving either strength or speed can increase power.

Most of the declines in muscle power in older age seems to be due to the speed component - or the reduced ability of muscles to contract quickly.

For this reason, resistance training with faster movement speeds is very effective for improving muscle power.

By prioritising speed, so-called “power training” improves both the force and speed abilities that directly influence physical function.

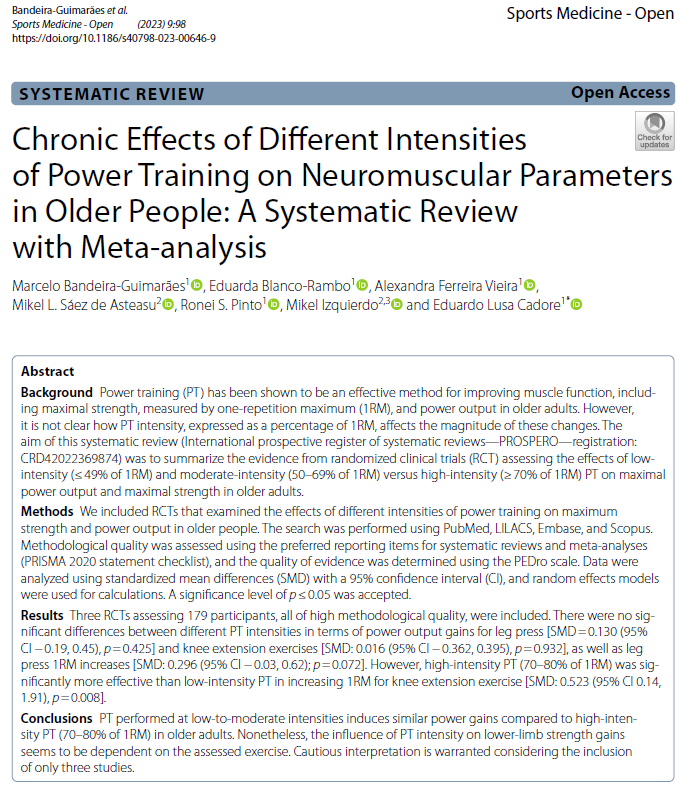

How much training is needed to improve muscle power?

The bottom line is that even small doses of power training can boost - well…muscle power.

But that’s not the sole benefit of training with faster movement speeds.

This also comes with added benefits of:

- Greater muscle mass and strength

- Improved balance and gait

- Better cognition

- Reduced falls

|

What’s more, all of these benefits are seen even in the most frail older adults.

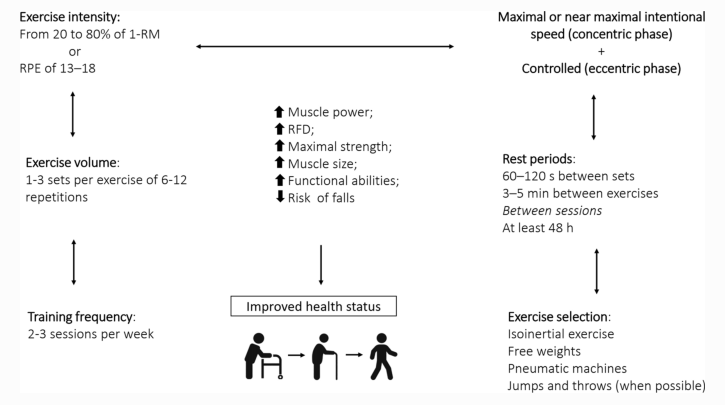

So - what does so-called “power training” actually look like?

Putting power training into practice

The essence of power training is resistance training with fast lifting (or concentric) movements followed by slow lowering (or eccentric) movements.

These faster movements can be performed on their own, or combined with “traditional” resistance training (with a more controlled speed) in the same session.

So - let’s break down some of the key variables:

Exercises

Even simple bodyweight exercises can provide enough resistance initially.

These movements can then progress to either free weight or machine variations, which are similarly effective.

Because muscles of the lower body are more susceptible to losses of strength and mass with ageing, it pays to focus on lower-body exercises (like squats, sit-to-stands, knee extensions).

Intensities (loads)

A range of intensities (loads) are effective with power training in older adults.

Even low to moderate intensity (40-60% 1-RM) loads can improve muscle mass, function, and reduce falls in frail older adults.

The caveat is that with heavier loads, movement speed slows down.

But so long as the intent to move fast is there, power can still improve:

|

Although a range of loads can be used, it's probably best to stick with lighter loads first, and progress to higher loads when capable.

Number of sets and frequency

Even small amounts of power training can be enough to see benefits.

This means it can help to start with a "minimal" dose, which can be as small as:

- 1 set per exercise

- 6-12 repetitions per set

- 2 sessions per week

From there, the exercise "dose" can be increased over time - for example to 3 sets per exercise and 3 sessions (per muscle group) per week.

But for most people, sticking with (at least) a minimal dose may offset much of the declines in muscle power with ageing.

Rest periods

With power training, the ability (or at least the intent) to move fast is important.

But with fatigue, this becomes compromised.

This is where rest periods become important.

In general, 1-2 minutes rest between sets (and 3-5 minutes between exercises) is enough to allow faster movement speeds to be maintained.

For the same reason, it's best to leave 48 hours between sessions with the same muscle groups.

Faster movement speeds are not without their risks.

One caveat with power training is faster movement speeds (especially with lighter loads) can increase injury risk in those with joint degeneration.

So, it's important to screen for conditions like tendinopathy, osteoarthritis, or abdominal hernias prior to starting power-based training.

Despite this, evidence suggests injury rates and adverse events with this type of training are usually low.

And even where faster-speed training is not appropriate, resistance training with controlled speeds may be a more suitable option.

Despite the known benefits, power training remains underused in practice.

Power training is effective across a wide spectrum of older adults, from those who are healthy to frail - and even those who are hospitalised.

But uptake of power training remains low, particularly in clinical settings.

There are many possible reasons for this, including:

- Unfamiliarity among clinicians

- Equipment limitations

- Fear of injury

Overcoming these challenges is key to boosting uptake of power training.

And in turn, preserving what's probably our most critical physical capacity across the lifespan.

Thanks for reading!

See you next week,

Jackson

If you've got a moment, I'd love to hear your thoughts on this edition of The Weekly Exerciser.

Send me a quick message or email - I'll reply to every one!

PS: Did someone forward you this email? You can sign up to The Weekly Exerciser here.

IMPORTANT:

The information contained herein is of general nature only and does not constitute personal advice. You should not act on any information without considering your personal needs, circumstances, and objectives. Any exercise program may result in injury. We recommend you obtain advice specific to your circumstances from an appropriate health professional before starting any exercise program.

The Weekly Exerciser

A weekly newsletter with actionable tips to make exercise easier.